I Stand in the Void

The void is not necessarily a nonexistence, it is the other face of existence itself; the moment before fullness, a space where the boundary between the inside and outside dissolves, leaving the self free of masks while it ponder upon what was and what is yet to come.

From the earliest philosophers, interpretations diverged: Aristotle claimed that “nature abhors a vacuum,” while Lao Tzu saw emptiness as the very source of value; the cup is useful because of its empty space, and the door functions because of the gaps it covers or shapes. As for me, I discovered that the void is not a lack but a condition of possibility.

Yet, what does the void mean for a Palestinian in Gaza?

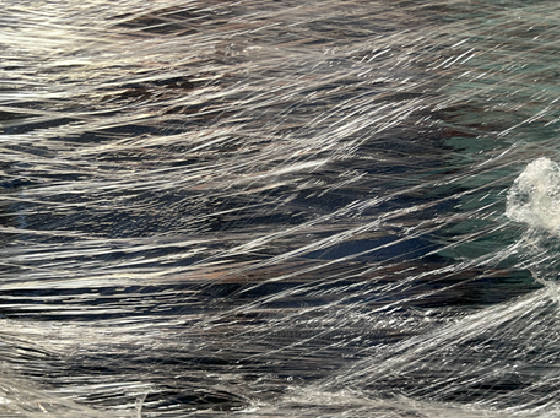

How can one speak of “empty space” in a reality crowded with displacement, where even the acoustic space is colonized by the buzzing of drones, the rumble of tanks, the ever-present roar of war? In truth, Palestinians inhabit an inverted void: an inner emptiness heavy with fear and loss, and an outer emptiness thick with ruins and masses of the displaced.

In times of annihilation, the void becomes an existential trial. We may rush to fill it to escape its weight, or we may leave it open, searching within it for new possibilities, looking for the very act of survival. Even birth itself is a void, a fragile seed carrying the possibility of new life. In the heart of war, women gave birth, as if to say that the void is not death but a passage toward creation.

The void is also time itself when it weighs upon us: the moment of facing unanswerable questions: Where did our friends who martyred go?

Why can’t we gather after work anymore?

How did I become without a home, without even the ability to express myself?

And yet, when a city is demolished and space seens emptied, transformation begins. In ruined streets, shops reopen, lovers return to their meetings, and Gaza finds again its coffee, its ice cream, its unmistakable scent. From beneath the rubble, it rises like a phoenix, brushing off the dust to rebuild itself again.

So I ask: is the void a necessary condition for feeling time, especially the time of annihilation?

And where does a Palestinian draw hope from, when every surrounding place is wrecked again and again by bombing?

أقف في الفراغ

الفراغ ليس انعدامًا بالضرورة، بل الوجه الآخر لفكرة الوجود ذاتها. إنه اللحظة التي تسبق الامتلاء، مساحة يتلاشى فيها الحدّ الفاصل بين الداخل والخارج، ليجد الإنسان نفسه عاريًا من كل الأقنعة، في مواجهة ذاته المعلّقة بين ما كان وما سيكون.

منذ الفلاسفة الأوائل، اختلفت القراءات: أرسطو قال إن “الطبيعة تمقت الفراغ”، فيما رأى لاو تزو أن الفراغ هو ما يمنح الأشياء قيمتها؛ الكوب لا يكون مفيدًا إلا بفراغه، والباب لا يؤدي وظيفته إلا بفسحته. وأنا في بحثي عن معنى الفراغ وجدت أنه ليس نقصًا، بل شرط إمكان.

لكن، ما معنى الفراغ بالنسبة للفلسطيني في غزة؟

كيف يمكن أن تتحدث عن “مساحة فارغة” في واقع يكتظ بالنازحين، ويُستعمَر فيه حتى الفضاء الصوتي: من أزيز الطائرات المسيّرة إلى دمدمة الدبابات؟ في الحقيقة، يختبر الفلسطينيون فراغهم بطريقة معكوسة: فراغ داخلي مكتظ بالخوف والفقد، وفراغ خارجي مثقل بالدمار والحشود.

في زمن الإبادة، يصبح الفراغ اختبارًا وجوديًا. قد نملأه بأي شيء هروبًا من ثقله، أو نؤجّل ملأه لنبحث في داخله عن احتمالات جديدة، عن “فعل النجاة”. في هذا السياق، حتى الولادة نفسها لحظة فراغ: نطفة صغيرة تحمل إمكانية حياة جديدة. هكذا أنجبت النساء في قلب الحرب، وكأنهن يرددن أن الفراغ ليس موتًا، بل بوابة للخلق.

الفراغ أيضًا هو الزمن حين يتثاقل علينا: لحظة مواجهة الأسئلة التي لا جواب لها: إلى أين ذهب أصدقاؤنا الشهداء؟ لماذا لم يعد يجمعنا المساء بعد العمل؟ كيف صرت بلا بيت، بلا قدرة حتى على التعبير؟

لكن حين تُهدم مدينة، ويبدو المكان فراغًا، يبدأ التحول. في الشوارع المدمرة، تعود المحلات لتفتح أبوابها، يعود العشاق إلى اللقاء، وتعود غزة لتصنع قهوتها وآيس كريمها ورائحتها الخاصة. من بين الركام، تنهض كالعنقاء، تزيح الغبار وتعيد البناء.

لذلك أسأل: هل الفراغ شرطٌ أساسي للإحساس بالزمن، زمن الإبادة بالذات؟ ومن أين يأتي الفلسطيني بالأمل، حين تُفرغ المساحات من حوله بفعل القصف المستمر؟